This is my second post on “How to Teach Model United Nations.” Every week, I will share teaching tips, lesson plans, and classroom activities on various Model UN topics and skills.

This series is geared towards US-based high school and middle school teachers who are new to Model UN, interested in starting a club at their school, or looking for ideas on how to use Model UN in the classroom.

Which country will you represent at your next Model UN conference?

When you and your students register for a Model UN conference, one of the first pieces of information you’ll receive from the conference organizers is your country assignment, e.g. what country (or countries) your students will represent at the conference.

This information also tells you what committees you’re in and what topics you’ll debate. Once you know your country, your students can start preparing for the conference. And students who are representing the same country (most likely all of your students if you’re leading a small club) can work together and pool their research efforts.

There are various reasons for learning how to research a country:

- As representatives of their assigned country, your students should know something about their country! Especially the most basic facts: where it is, who the leaders are, how many people live there, etc. You lose credibility in committee if someone asks you these basic questions and you just don’t know.

- Many Model UN conferences require students to submit a position paper before the conference. In this paper, students will describe their country’s policies and proposed solutions regarding the topics they will debate at the conference. The first step to writing this paper is researching your country.

- One of the reasons to participate in Model UN is to learn about the world. Country research is an opportunity for your students to gain perspective on what it’s like in other parts of the world.

- Research is a skill that students will use throughout grade school and university, as well as their careers.

So if you’re a teacher or parent who’s new to Model UN, how do you teach your student how to research a country? Read on!

How many countries in the world are there?

I asked this question to kick off a lesson on country research that I taught the other day. Most of my students offered a random number between 100 and 200, which is what I expected. One student said 193 — which is almost correct, but not quite. (Note: I’m going to use the terms “state” and “country” interchangeably in this post.)

There are 193 member states in the United Nations, but there are countries in the world that are not UN member states.

- Taiwan used to be a UN member state and it represented China when the UN was founded. But in 1971, the General Assembly recognized mainland China – the People’s Republic of China – as “the only legitimate representative of China to the Untied Nations,” and it expelled Taiwan. (General Assembly Resolution 2758)

- Kosovo declared independence in 2008, but the international community is divided over whether to consider Kosovo a state.

- The Holy See is more commonly referred to as the Vatican. It has permanent observer status at the UN, meaning it participates in debate but does not vote on resolutions.

- Palestine is seeking UN membership, as I described in last week’s post. And as someone pointed out in the comments, Palestine is currently a “non-member entity,” and if it cannot obtain full membership, then it will seek to become a “non-member state.”

You and your students might think that the number of countries in the world is a straightforward answer — i.e. a single number — but it’s not. It depends on who you ask and what source you look up. But that leads us to another, more important question: what defines a country or state?

In international law, the 1933 Montevideo Convention lists four criteria for defining a state:

“(a) a permanent population;

(b) a defined territory;

(c) government; and

(d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.”

There’s some debate over whether the Convention is good law. Foreign Policy featured a couple essays on whether it qualifies Palestinian statehood (here and counter-argument here). Regardless, the Convention’s four criteria provide a framework for not only defining a country, but how to research it.

Country Profile: Geography and History

There are four areas of a country that your students should research:

- Physical Geography (“defined territory”)

- Cultural Geography (“permanent population”)

- Political Geography (“government”)

- Economic Geography (“capacity to enter into relations with the other states” e.g. trade)

Geography represents different features about a country today, but students should also learn how those features have changed over time and why. In addition to country geography, they should study a country’s history. This combination of geography and history amounts to a country profile.

To help your students explore their country, I’ve prepared this handout. It features 20 frequently asked questions about country geography. It also has directions for preparing a brief presentation about their country. This handout could be used to help students practice their research skills, as well as public speaking.

The starting point for country research is the CIA World Factbook. This was the first website I was told to look at when I started Model UN, and every MUNer I know uses it for their country research. Information from the CIA World Factbook will answer most of the questions in the handout above.

I also think Wikipedia is a good primer for researching your country. It should not be quoted or cited, especially in academic writing, and you should emphasize that to your students. But for Model UN, and for introductory-level research, Wikipedia often provides a good overview of a topic, and more importantly, it can lead your students to more robust sources of research, e.g. primary sources. I would treat Wikipedia like a background guide in Model UN: it’s not meant to be authoritative; rather, it’s a starting point for your research.

Additionally, see if your country’s ministry of foreign affairs has a website, which will often contain information on current events and history, as well as speeches by government leaders. And, online news sources, particularly news aggregators like Google News and Yahoo! News, should round out your students’ country research.

Classroom Activity: Country Board

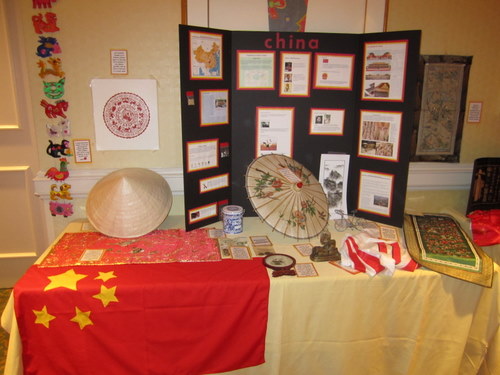

At the Montessori MUN Conference in NYC, which draws 4th grade to 9th grade students from around the world, schools prepare for the conference by creating posters and dioramas of the countries they represent. One school even created a 1/100th-size replica of the UN!

This is a great activity for younger students to teach them country research and engage them in world affairs.

Do you have any questions about country research? Or would you like to share any tips on teaching students how to research their country? Leave a comment below!