One of the most common questions I get from newer delegates and teachers is how to write a resolution. A resolution contains all the proposed solutions to a topic. Learning to write a resolution is very important because the ultimate goal of the committee sessions is for delegates to come up with written solutions to the problems they are trying to solve. The primary authors of the resolution will also be recognized as the leaders in the committee which distinguishes them from everyone else for awards.

This Model UN Made Easy article will explain the basic “who, what, when, where, and why” of a resolution. It will then show how a resolution looks like and explain how to write one. It will also explain how to make amendments to a resolution. Finally, it will provide some tips to get started on writing a resolution.

Basics of a Resolution

Who: Who writes a resolution? Any delegate in the committee can write a resolution (although in rare instances an observer state is not allowed to directly write a resolution). The author of a resolution is called a sponsor. Most resolutions have multiple sponsors because it takes a group of countries to share good ideas and to come to a consensus. Some conferences allow delegates to sponsor multiple resolutions for each topic while others only allow delegates to sponsor one per topic.

What: What is a resolution? A resolution is a document that contains all the issues that the committee wants to solve and the proposed solutions to that issue. It’s called a resolution because that’s what the United Nations calls the documents they produce. Technically, the resolution should be called a draft resolution before it is voted upon and then called a resolution after it is successfully passed during voting bloc.

When/Where: When and where are resolutions written? Most conferences require students to write resolutions during the conference. Specifically, resolutions are usually written during unmoderated caucus (sometimes called informal caucus) where delegates are free to roam around the committee to collaborate on ideas with each other, and sometimes students work outside in hallways or computer labs as well. Resolution-writing becomes more focused during the latter sessions of committee when different country policies are clear and different ideas have been mentioned already. These conferences will not allow any pre-written resolutions. A few conferences have “docket-style” debate. This is when students are required to submit resolutions to the conference in advance and the chairs pick the best ones and put them into a docket. The delegates focus only on the resolutions in the docket when they get to the conference and work on amending them.

Why: The ultimate purpose of a committee session is to pass a resolution. All the speeches, debate, negotiation, and teamwork is supposed to lead up to a resolution which contains all the proposed solutions to the issue. The resolution(s) that the majority of the committee agrees upon will be passed during voting bloc and the sponsors will be informally commended for building consensus on good ideas. Most conferences allow multiple resolutions to pass as long as they do not contradict each other, but a few conferences allow only one resolution to pass.

How to Write a Resolution

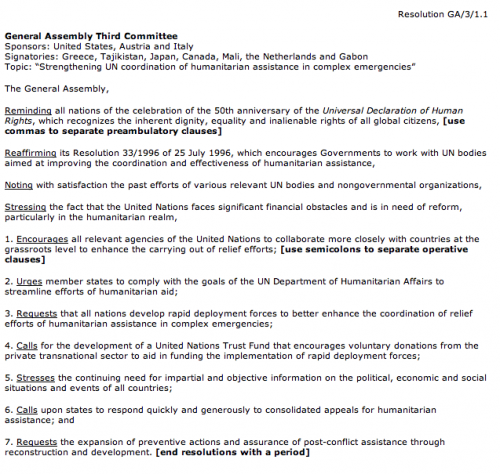

How: how do I write a resolution and what does the format look like? First, here is an example of how a resolution looks like from UNA-USA’s website:

A resolution is actually really simple to write. It has three main parts: the heading, the pre-ambulatory clauses, and the operative clauses. We’ll break down the example above into these three parts below.

1. Heading

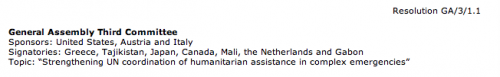

The heading contains four pieces of information: the committee name, the sponsors, the signatories, and the topic (not necessarily in that order depending on each individual conference’s rules).

The committee name and topic should be self-explanatory. The sponsors are the authors of the resolution. The signatories are other delegates in the committee who do not necessarily agree with the resolution but would like to see it debated. Most conferences require a minimum number or percentage of sponsors and signatories (or a combination of both) before a resolution can be presented — this encourages consensus-building. You will also notice some numbering (on the top right corner in the example). This is usually provided by the committee chair and is just a way to number the different resolutions — usually by the order they are received or approved — so that delegates can easily differentiate or reference them.

2. Pre-ambulatory clauses

The pre-ambulatory clauses states all the issues that the committee wants to resolve on this issue. It may state reasons why the committee is working on this issue and highlight previous international actions on the issue. Pre-ambulatory clauses can include:

- Past UN resolutions, treaties, or conventions related to the topic

- Past regional, non-governmental, or national efforts in resolving this topic

- References to the UN Charter or other international frameworks and laws

- Statements made by the Secretary-General or a relevant UN body or agency

- General background info formation or facts about the topic, its significance, and its impact.

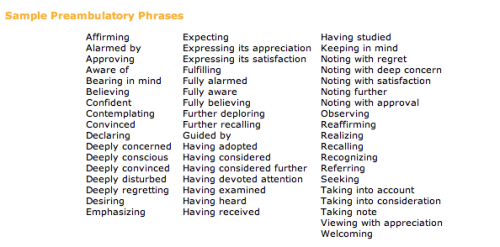

It’s very simple to write a pre-ambulatory clauses. First, take a statement that you want to write about (perhaps an issue you want to solve or a specific fact from one of the five bullet points above). You then take that statement, combine it with an underlined pre-ambulatory phrase, and end it with a comma. Here are some example pre-ambulatory phrases from UNA-USA’s website that you can choose from:

For example, my country wants to address the issue of how HIV/AIDS has spread rapidly in sub-Saharan Africa. I pick a pre-ambulatory phrase from above — I’ll use “Alarmed by” — and then I combine it to say:

Alarmed by the 17% increase in HIV/AIDS contraction among sub-Saharan African countries in the past five years,

Strategy Tip: In general, you want fewer pre-ambulatory clauses than operative clauses. More operative clauses convey that you have more solutions than you have problems.

3. Operative clauses

Operative clauses state the solutions that the sponsors of the resolution proposes to resolve the issues. The operative clauses should address the issues specifically mentioned in the pre-ambulatory clauses above it.

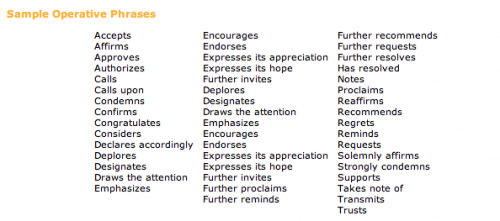

It’s very simple to write an operative clause. First, take a solution that you want to include in the draft resolution. You then take that solution, combine it with an underlined operative phrase, and end it with a semicolon (the last operative clause ends with a period). Operative clauses are also numbered. This differentiates them from pre-ambulatory clauses, helps show logical progression in the resolution, and makes the operative clauses easy to refer to in speeches and comments. Here are some example operative phrases from UNA-USA’s website that you can choose from:

For example, my first solution is to distribute low-cost medicines for HIV/AIDS to sub-Saharan African countries. I pick an operative phrase from above — I’ll use “Calls upon” — and then I combine it and number it to say:

1. Calls upon the developed countries and major pharmaceutical countries to provide low-cost, generic medicines for HIV/AIDS to sub-Saharan African countries;

Strategy Tip: Usually more details in an operative clause will make it stronger or at least make the idea more clear to other delegates. A simple way to strengthen each operative clause is to answer the “who, what, when, where, why, and how” of each resolution. These details can actually be broken down into sub-operative clauses underneath the main operative clause.

Amendments

UNA-USA’s website already provides a great explanation of what amendments are, so I will copy it below:

Approved draft resolutions are modified through amendments. An amendment is a written statement that adds, deletes or changes an operative clause in a draft resolution. The amendment process is used to strengthen consensus on a resolution by allowing delegates to change the operative clauses (the pre-ambulatory clauses can not be modified). There are two types of amendments:

1. A friendly amendment is a change to the draft resolution that all sponsors agree with. After the amendment is signed by all of the draft resolution’s sponsors and approved by the committee chair, it will be automatically incorporated into the resolution.

2. An unfriendly amendment is a change that some or all of the draft resolution’s sponsors do not support and must be voted upon by the committee. This also refers to delegates who did not write this resolution at all but see potential in it as long as several changes are made to it. The sponsors of the amendment will need to obtain a required number of signatories in order to introduce it. Prior to voting on the draft resolution, the committee votes on all unfriendly amendments.

Writing an amendment is very simple. All you have to do is make an operative clause that adds, deletes, or changes an operative clause in a draft resolution. Examples include:

- Adds an operative clause that reads “14. Encourages all Latin American countries to…”

- Deletes operative clause 9.

- Changes operative clause 1 to read “1. Calls upon the Red Cross to provide low-cost medicines…”

Tips to Get Started

1. I recommend printing the page from UNA-USA’s website with all the pre-ambulatory and operative phrases and putting that document in your Research Binder. This will make the phrases very easy to reference to when delegates need to write them in committee. Most major conferences also provide their own list in their conference program or website.

2. I also recommend practicing translating ideas into pre-ambulatory and operative clauses if you are not used to it already. You can do this with your class — have someone mention an issue within their topic and then have students come up with a pre-ambulatory clause for it or have someone propose a solution and then have students come up with different operative clauses for it. Sooner or later, you will become fluent in writing them and have memorized your favorite clauses so that you can easily turn any statement into a clause.

3. If this is too basic, then read our article on How to Debate Resolutions or get our book How to Win Awards in Model United Nations which has a chapter discussing strategies for resolutions.