Ever since the Puerto Rico Lo Hace Mejor article came out, we’ve been curious to check out the Puerto Rican circuit. Puerto Ricans are well known on the college circuit with influential leaders such as Rodolfo Diaz at Harvard (Colegio San Ignacio), Bianca Faccio at U.Penn (Colegio Puertorriqueño de Niñas), and Cristina Diaz-Torres at NYU (Academia Maria Reina). And they are well known at the high school level as well, with five teams ranking in the top 150 last year after strong performances at ILMUNC and NAIMUN. It turns out the common connection here is La Federación, one of two formal Model UN circuits that exist in Puerto Rico (the other is El Congreso).

There’s nothing like La Federación in the entire world of Model UN. The regions with the closest thing to a formal local circuit would be Southern California where most of the schools attend each other’s conferences, or the THIMUN-affiliated conferences where standards exist across conferences; overall Puerto Rico looks most similar to Southern California. So it’s important to understand the structural lessons behind La Federación because the development of a local circuit is something that can greatly benefit other local Model UN communities if they emulate it. All the Puerto Rican delegates also kept emphasizing how different they do Model UN, and I’ve also included an analysis of some cultural differences.

5 Structural Lessons for Creating a Circuit

1. There is a formal set of schools. In La Federación, there are seven schools that are in a formal circuit (Academia Maria Reina, Baldwin School of Puerto Rico, Colegio Marista, Colegio Puertorriqueño de Niñas, Colegio San Ignacio de Loyola, Saint John’s School, and TASIS School of Dorad0). All these schools participate in the same standardized circuit of conferences, and five of the seven typically travel together to NAIMUN. This creates a tight-knit circuit as everyone knows each other, sets standards across conferences, and allows participants from each school the priority to register for the conferences. If there is capacity left at the conference, then other schools outside La Federación can register as guest schools.

2. There is a set schedule of rotating hosts schools with chairs drawn from all schools. All schools in La Federación attend the same five conferences each year, with the host for the five conferences rotating among the seven member schools. The schedule is all set in advance so that there’s no competition for dates among the schools. Chairs are drawn from among the best delegates from all member schools and each dais contains chairs from different schools to ensure that there is no bias in awards. All the chairs are trained the same way before the season starts to ensure standardization. Most Puerto Rican students actually prefer participating as delegates instead of chairing and will end up chairing only once or twice in the season, so there is actually a pool of 40-50 chairs that rotate among the La Federación conferences.

3. Scoring is standardized with a points system and rubric. La Federación uses a points system to determine awards and there is a rubric for all the chairs. There is also a rubric for position papers as well, and I saw the rubric and scores attached to the position papers as they were handed back. I noted that Puerto Rico is the only other place in the world besides Southern California that uses a scoring system. But unlike Southern California, the rubrics are standardized across conferences whereas in Southern California each conference sets its own rubric. Overall, there is a strong emphasis on transparency, and like Southern California schools the Puerto Rican delegates sometimes get frustrated by the non-transparent holistic judging that takes place on East Coast conferences.

4. Fees are low, standardized, and re-invested into the delegates. The conference fees are standardized across conferences and are set to be not very expensive. This is one of the biggest strengths of La Federación as conferences won’t engage on a pricing war like how conferences sometimes do in the mainland (prices have continually increased in the mainland). In fact, one advisor mentioned that the fees are meant to break-even and not to generate fundraising revenue or profit. The fees were re-invested in the delegates as the conference provided snacks and drinks and the chairs did a good job in decorating the committees.

5. Topics are selected thematically and typically don’t repeat in the circuit. The conferences typically prefer crisis committees and don’t simulate too many traditional UN committees. Instead, they have thematic committees (e.g. political, economic, historical) and pick a committee to match the theme. For example, the economic committee at this St. John’s School MUN Conference was the G20 Summit. Topics typically aren’t repeated across conferences for the year.

Cultural Differences in Puerto Rico

Puerto Ricans like to emphasize that they do Model UN differently. The conferences contain most of the major concepts in Model UN, but here are some differences:

1. The students are truly bilingual. This is perhaps Puerto Ricans’ biggest competitive advantage. The speeches can be made in either English or Spanish in any committee and everyone understands it fluently. In theory, most of the conferences have Spanish as the default language with one conference being designated as the English competition. In practice, both languages are used simultaneously in committee with a slight preference for Spanish.

2. The focus is on debating. I found it interesting when I asked delegates during my Advanced Strategies workshop on what are the three most important sections to do research on and the response was 1) Background of Topic, 2) Country Policy, and 3) Your Top Opponents’ Arguments. The emphasis in committee is on the debating aspects, and actually the topics are formally divided into sub-issues on the agenda and the committee will debate on each sub-issue in the order that it’s set in the agenda. Students explained this is cultural as this is how politicians debate on the island.

3. The speaking style is more animated. Students tend to speak louder and faster (sometimes very fast). They also tend to be more animated and prefer to pace in front of committee instead of standing still when delivering speeches. As one parent pointed out, there are pros and cons to these styles but nevertheless it is a reflection on the Puerto Rican culture and passion for Model UN.

4. The chairs are activist chairs. The chairs are highly involved in directing the flow of debate and they tend to bang the gavel a lot (actually both chairs have their own gavel so there’s even more banging) compared to most chairs in North America. This is in comparison to the facilitator style of chairing which allows delegates to direct more of the flow of debate and to deriving authority through presence instead of banging the gavel.

5. Delegates must ask “Delegates will you accept my question?” before addressing the speaker. Questions after a speech are not uncommon in Model UN, but this is the first time I’ve heard this phrase used before a delegate can ask the speaker a question. Chairs can take off diplomacy points if a delegate does not ask this question. I’m not sure where it’s derived from but I suspect it’s from some type of parliamentary debate.

6. Parents are supportive and some are even Model UN alumni. Parents were very supportive of the conference, with parents from multiple schools volunteering at this conference. The conference even recognized each parent with flowers during Closing Ceremonies. Many parents were also in attendance during Closing Ceremonies to observe. I also met a few parents who did Model UN when they were students. All this goes to show that there is a strong cultural emphasis on Model UN and that the activity is highly valued on the island. Besides Southern California where parents lead influential Model UN booster clubs, there is nowhere else in the world where parents are this involved with Model UN.

Like usual, our liveblog features photos of delegates and staff in action:

It’s important to participate in the debate since points are given for every action. Delegates raise their placards to ask a question to another delegate here in the International Drug Control Treaty 2012

The Chair of the International Drug Control Treaty 2012 looks to select the next speaker. Note the Spanish names for the countries on the placards and the Spanish text in the draft resolution projected in the back.

Delegates must ask the speaker for permission before asking a question. “Delegate will you accept my question?”

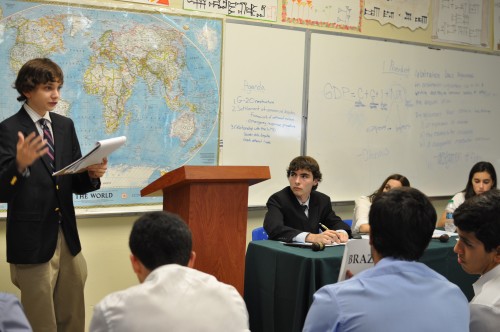

A good number of delegates preferred to pace around the front of the room when making their speeches

Co-delegates strategize together. Delegates were paired up in every committee including cabinets such as the Indian Independence Movement where they would share one cabinet member.

A delegate speaks during a moderated caucus to respond to a crisis in the Indian Independence Movement

Another delegate speaks during a moderated caucus to respond to a crisis in the Indian Independence Movement

A guest speaker demands Sikh independence as part of an ongoing crisis in the Indian Independence Movement

St. John’s School MUN Secretary-General Jose Augusto del Rosario Cardona enjoys watching the committees in action

This was not the first time Best Delegate has met these students, and this will surely not be the last as we’ll most likely see them at conferences such as NAIMUN and ILMUNC. Good luck with the rest of the season!

Special thanks to Saint Johns MUN Moderators Amelia O’Neill and Olga Alfonso for having me attend, Saint John’s MUN Secretary-General Jose Augusto del Rosario as well as Soraya, Beatriz, Syra and the rest of the staff for showing me around the conference, Julian Bava for initially inviting me to visit, and to all the students, moderators, and parents who thanked me for my presentations and workshops.